Chapter 1. Setting the Stage: Life Before Montevideo

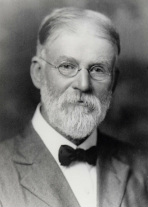

Celia Campbell Stay

By 1862, relations between the U.S. government and Dakota had deteriorated. Annuity payments were late, traders weren’t extending credit due to unpaid debts, and the Dakota were hungry. On August 17th, 1862, four Dakota men killed a family near Acton, Minnesota, ushering in the start of the U.S.—Dakota Conflict. After heated debate among tribal leaders, the Dakota, under the leadership of Little Crow, opted to go to war. The following day, the Lower Sioux Agency and settlers living in that vicinity were attacked. In ensuing days, the Upper Sioux Agency, Fort Ridgely, New Ulm and other areas were attacked as the hostilities spread throughout the Minnesota Valley and southern Minnesota, extending into Dakota Territory. An estimated 600 white settlers were killed during the conflict.

The Dakota engaged the U.S. Army at Fort Ridgely and gained major victories at Birch Coulee and Redwood Ferry. However, under the leadership of Colonel Sibley, the Army handed the Dakota a decisive defeat at Wood Lake. While the battle was being waged, Dakota chiefs who wanted no part in the hostilities—including Chief Red Iron (Mazasha), and his brothers Mazamani and Akipa—took control of captives, ultimately delivering them to Sibley at Camp Release near Montevideo. Shortly thereafter, the Dakota were expelled from the state, and the Upper Minnesota Valley was opened for settlement.

The Dakota engaged the U.S. Army at Fort Ridgely and gained major victories at Birch Coulee and Redwood Ferry. However, under the leadership of Colonel Sibley, the Army handed the Dakota a decisive defeat at Wood Lake. While the battle was being waged, Dakota chiefs who wanted no part in the hostilities—including Chief Red Iron (Mazasha), and his brothers Mazamani and Akipa—took control of captives, ultimately delivering them to Sibley at Camp Release near Montevideo. Shortly thereafter, the Dakota were expelled from the state, and the Upper Minnesota Valley was opened for settlement.

Chapter 2. Prominent Montevideans

Lycurgus R. Moyer

Montevideo owes it existence and historic vitality to the foresight, dedication, and hard work of its citizens. The work ethic of Yankees and immigrant families—Norwegians, Germans, Irish, and other nationalities—built the town.

As in all successful towns, individuals emerged to lead Montevideo forward, recrafting its image as a farm town and pioneer village into a modern, prosperous, and cultural locale. These visionary leaders in large part constructed the economic and cultural engine that was Montevideo; through its farmers, store owners, factory workers, educators, and housewives, the town’s engine was fueled.

Within this chapter, we profile a small number of Montevideo’s most prominent early leaders. These include “town-builders” George W. Frink and Cornelius I. Nelson, along with Lycurgus R. Moyer, Charles H. Budd, Reverend Ole E. Solseth, Frank and Celia Stay, and the Henry Gippe family.

As in all successful towns, individuals emerged to lead Montevideo forward, recrafting its image as a farm town and pioneer village into a modern, prosperous, and cultural locale. These visionary leaders in large part constructed the economic and cultural engine that was Montevideo; through its farmers, store owners, factory workers, educators, and housewives, the town’s engine was fueled.

Within this chapter, we profile a small number of Montevideo’s most prominent early leaders. These include “town-builders” George W. Frink and Cornelius I. Nelson, along with Lycurgus R. Moyer, Charles H. Budd, Reverend Ole E. Solseth, Frank and Celia Stay, and the Henry Gippe family.

Chapter 3. Commerce

Citizens State Bank

Business supplied the economic life-blood of the growing community. When Montevideo was young, business was centered around the mill on what is now North First Street. A handful of businesses—hotel, grocery, law office, blacksmith and others—lined the street, providing critical supplies to people living in the immediate area.

The arrival of the railroad in 1878 fueled the economic vitality of Montevideo. It brought both settlers and needed supplies, while providing an opportunity to export products to external markets. With the onslaught of immigrant settlers, agricultural production grew rapidly. Products emanating from farms fueled the establishment of businesses that made use of these supplies. In turn, local businesses provided materials necessary for farmers, Montevideans, and the large numbers of immigrants that were arriving in or passing through the village.

The arrival of the railroad in 1878 fueled the economic vitality of Montevideo. It brought both settlers and needed supplies, while providing an opportunity to export products to external markets. With the onslaught of immigrant settlers, agricultural production grew rapidly. Products emanating from farms fueled the establishment of businesses that made use of these supplies. In turn, local businesses provided materials necessary for farmers, Montevideans, and the large numbers of immigrants that were arriving in or passing through the village.

Chapter 4. Agriculture

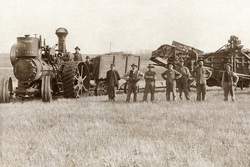

Threshing Crew

With the opening of Chippewa County for settlement in 1865, people began streaming into the region. The Homestead Act of 1862 provided 160 acres of land free of charge to settlers if they stayed with and improved upon the land for a minimum of five years. This lure, for European immigrants and Yankees alike who were accustomed to small farms on poor, rocky soils, was all too enticing.

The early immigrant and Yankee farmers were self-sufficient, and farms provided all the necessities of life. A diversity of livestock, grain crops, gardens, and orchards yielded the necessities of life. If lucky, excess could be sold to neighbors, residents of Montevideo, or shipped via the rails to metropolitan centers. Free land, good soil, and a strong work ethic permitted farmers, and in turn Montevideo, to prosper.

The early immigrant and Yankee farmers were self-sufficient, and farms provided all the necessities of life. A diversity of livestock, grain crops, gardens, and orchards yielded the necessities of life. If lucky, excess could be sold to neighbors, residents of Montevideo, or shipped via the rails to metropolitan centers. Free land, good soil, and a strong work ethic permitted farmers, and in turn Montevideo, to prosper.

Chapter 5. Education and Religion

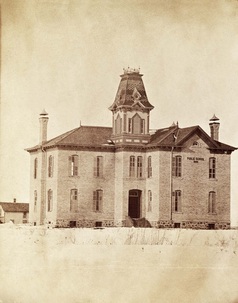

Montevideo Public School

Education and religion played a critical role in the lives of early Montevideans. They were the “social glue” that held families and the community together. Moreover, they provided for a firm foundation upon which youth could build moral, ethical, and economically

vibrant lives. A major driver among immigrants was to ensure that their children were better off

than they were; education and religion were integral to that end.

In Montevideo, a diversity of churches arose to meet the needs of its citizens. Among the first were the First Congregational (organized in 1871), Methodist Episcopal Church (1871), Baptist Church (1877), Norwegian Lutheran Church (1879), Grace Episcopal Church (1880) and St. Joseph’s Catholic Church (1888).

The first school classes in Montevideo were held in the home of Cornelius Nelson in 1870, with Miss Florence Stewart as teacher. As the village’s population grew, schools were regularly built and enlarged. Montevideo’s first wood frame school, built in 1872, was replaced in 1880 by a two-story brick school on the bluff overlooking the Chippewa Valley; in 1902, a brick high school was built adjacent to it. Thereafter, Hillcrest and Sibley elementary schools were built. To address the need, one-room country schools were built across the county—usually four per township. At one point, 90 public schools were in operation across Chippewa County.

vibrant lives. A major driver among immigrants was to ensure that their children were better off

than they were; education and religion were integral to that end.

In Montevideo, a diversity of churches arose to meet the needs of its citizens. Among the first were the First Congregational (organized in 1871), Methodist Episcopal Church (1871), Baptist Church (1877), Norwegian Lutheran Church (1879), Grace Episcopal Church (1880) and St. Joseph’s Catholic Church (1888).

The first school classes in Montevideo were held in the home of Cornelius Nelson in 1870, with Miss Florence Stewart as teacher. As the village’s population grew, schools were regularly built and enlarged. Montevideo’s first wood frame school, built in 1872, was replaced in 1880 by a two-story brick school on the bluff overlooking the Chippewa Valley; in 1902, a brick high school was built adjacent to it. Thereafter, Hillcrest and Sibley elementary schools were built. To address the need, one-room country schools were built across the county—usually four per township. At one point, 90 public schools were in operation across Chippewa County.

Chapter 6. Government Services

Montevideo Fire Department #1

When settlers first arrived in what is now Montevideo and Chippewa County they, in large part, had to fend for themselves. Government services were minimal. Yet establishment of government on the frontier was one of the first actions undertaken by settlers.

As settlement continued, municipal and township elections were held throughout the county. The resulting growth in tax base enabled the county and its townships and villages to provide enhanced services to its citizens. These included water systems, fire departments, education, law, hospitals, roads, and postal services, among others.

Government also was responsible for development of the military. Chippewa County was organized after the Civil War, and played only a minor role during the Spanish-American War. Its first major engagement in enlisting local young men into the military came during the Great War (World War I), when 830 fighting recruits enlisted from Chippewa County. Forty-three are listed as having died during service, many from pneumonia before reaching the battlefield.

As settlement continued, municipal and township elections were held throughout the county. The resulting growth in tax base enabled the county and its townships and villages to provide enhanced services to its citizens. These included water systems, fire departments, education, law, hospitals, roads, and postal services, among others.

Government also was responsible for development of the military. Chippewa County was organized after the Civil War, and played only a minor role during the Spanish-American War. Its first major engagement in enlisting local young men into the military came during the Great War (World War I), when 830 fighting recruits enlisted from Chippewa County. Forty-three are listed as having died during service, many from pneumonia before reaching the battlefield.

Chapter 7. Leisure and Sports

Rose-Mandt Band

For hard-working residents of Chippewa County, free time was at a premium. However, social activities and interaction with neighbors and the broader community was an important part of life. Although, for many, churches provided weekly opportunities for social interaction, other more casual events rounded out the social calendar.

Festivities surrounding July 4th (and Syttende Mai for the Norwegians) and Decoration Day were widely attended for their parades, fireworks, and other associated events. Of course Easter, Christmas, and Thanksgiving provided much in the way of social engagement. The Chippewa County Fair annually brought people from far and wide to view the spectacles of the Midway and races at the track. For those inclined to join, civic organizations and fraternal groups provided both men and women opportunities to meet, socialize and collaborate on projects to the benefit of the city. Music was a long-standing tradition in Montevideo and throughout Chippewa County; conductors Shardlow and Pomroy gained special notoriety in this field from 1886 to 1930.

Festivities surrounding July 4th (and Syttende Mai for the Norwegians) and Decoration Day were widely attended for their parades, fireworks, and other associated events. Of course Easter, Christmas, and Thanksgiving provided much in the way of social engagement. The Chippewa County Fair annually brought people from far and wide to view the spectacles of the Midway and races at the track. For those inclined to join, civic organizations and fraternal groups provided both men and women opportunities to meet, socialize and collaborate on projects to the benefit of the city. Music was a long-standing tradition in Montevideo and throughout Chippewa County; conductors Shardlow and Pomroy gained special notoriety in this field from 1886 to 1930.

Chapter 8. Transportation

Surface roads provided the only real means of travel for early settlers. Although oxen were commonly used to draw wagons during the earliest days, horses quickly became the preferred animals. Roads, initially meandering point-to-point, were constructed along section lines after townships were organized. The biggest advances in road construction came after the arrival of automobiles. In the 1920s, large-scale highway construction was occurring in Chippewa County and across the state.

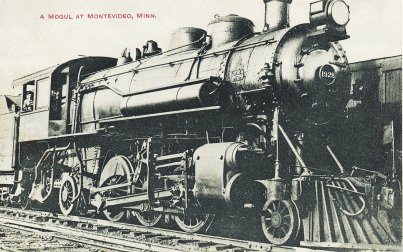

The arrival of the Hastings and Dakota Railroad (H&D) at Montevideo in 1878 was a major milestone for the new village; however, the impact of the railroad was not fully felt until 1887, when the Chicago Milwaukee and St. Paul moved its division offices and repair shops from Bird Island to the town. That action created 200 well-paying jobs, which ballooned to nearly 500 by 1923. A large roundhouse, associated buildings, and an extensive rail yard were established near the depot. In addition, stockyards were added to hold livestock for departure to slaughter facilities in South St. Paul, Austin, and Chicago.

The arrival of the Hastings and Dakota Railroad (H&D) at Montevideo in 1878 was a major milestone for the new village; however, the impact of the railroad was not fully felt until 1887, when the Chicago Milwaukee and St. Paul moved its division offices and repair shops from Bird Island to the town. That action created 200 well-paying jobs, which ballooned to nearly 500 by 1923. A large roundhouse, associated buildings, and an extensive rail yard were established near the depot. In addition, stockyards were added to hold livestock for departure to slaughter facilities in South St. Paul, Austin, and Chicago.

Chapter 9. Natural Disasters

Montevideo Flood

The early settlers of the Montevideo area, whether living in town or more rural areas, were often at the mercy of local weather conditions. Winters were severe, often followed by catastrophic flooding; summers were punctuated by severe thunderstorms, at times accompanied by tornados. Farmers and townsfolk alike persevered through self-sufficiency, by planning ahead, and by developing invaluable social networks with their neighbors. When times became difficult, neighbors pulled together, looked after each other, and together made it through to another day.

The most severe weather events became part of local lore. These included tornados, floods, blizzards, grasshopper plagues, severe thunderstorms and prairie fires. Few of these events, however, were captured photographically during the early days of Montevideo.

The most severe weather events became part of local lore. These included tornados, floods, blizzards, grasshopper plagues, severe thunderstorms and prairie fires. Few of these events, however, were captured photographically during the early days of Montevideo.